“I am not a prisoner of history. In the world through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself.”

― Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

Monsignor Brown with pupils at Embakwe mission school for Coloured children. Jesuit Archives, Harare, courtesy of Rob Burrett.

View full project here or an abbreviated version on the Social Documentary Network.

The quote by Frantz Fanon speaks powerfully to a central conflict of post-colonial, multi-racial identity: the tension between an individual's agency in defining themselves and the historical or social labels imposed by society. Shot over four months in Zimbabwe in 2023, this project amplifies the voices of senior members of Bulawayo’s fragmented 'Coloured' community, inviting personal reflections on a collective (hi)story often untold. It challenges us to confront, understand, and re-imagine: what does it mean to belong nowhere, yet to multiple worlds at once?

In Southern Africa, the weight of history remains heavy. One of the most enduring legacies of colonialism are the racial categories that continue to be perpetuated. In Zimbabwe, formerly the British colony of Rhodesia, society was segregated into 'White', 'Coloured', 'Asian', and 'African', straining social relations while reinforcing White superiority.

The term 'Coloured' broadly encompasses individuals of mixed European, Asian, Khoisan and Bantu ancestry, who historically occupied an intermediate position in the racial hierarchy. Zimbabwe is home to the second largest Coloured community in Anglophone Africa, after South Africa. Bulawayo, its second-largest city, is widely regarded as its cultural heartland.

To talk about Coloured people is to confront a multi-facetted reality. The violent dispossession and segregation of the colonial encounter. The anti-miscegenation laws that left mixed-race children in liminal spaces, burdened with shame. The intimate relationships, love letters hidden away by a system unwilling to acknowledge their truths. It also means celebrating the resilience and enduring humanity of a group navigating historical erasure.

Can we learn something from the bearers of memory—our elders—acknowledge our complex past, and perhaps, as Fanon advocates, reclaim our stories and ourselves?

My late grandmother, Audrey (Mama), allows her hair to be adorned with flowers. Of Asian, African, and European heritage, with family spread across the globe, she passed away shortly after this moment was captured. Troubled by the thought that her life and experiences would remain unrecorded, Mama became the inspiration for this project.

Uncle Petey, the fourth eldest out of thirteen children, reminisces: "We spoke Afrikaans at home. My parents and grandparents came up from South Africa by ox wagon in the early 1900s. To this day, I don’t know who my great-grandparents were…I’ll never know." Reflecting on his identity, he adds, "We are not White enough. We are not Black enough. Coloureds are just in between—like a sandwich."

Aunty Edna recalls a story passed down by her Grandmother (Gogo) about the Ndebele people's resistance during colonial invasion. As the White settlers pushed them into the swampy Matopos Hills, they fled while singing a powerful refrain: “The white man is running after us, I am going to die! But he must know that this will be my country.”

A photograph of Aunty Edna's grandfather and his daughters rests on her dimly lit mantelpiece. "Our grandfather was one of the few White men who stayed with his Coloured children until the end," she reflects. "He often said, 'There will come a time when the whole world will be mixed—everyone will be 'half-breeds'".

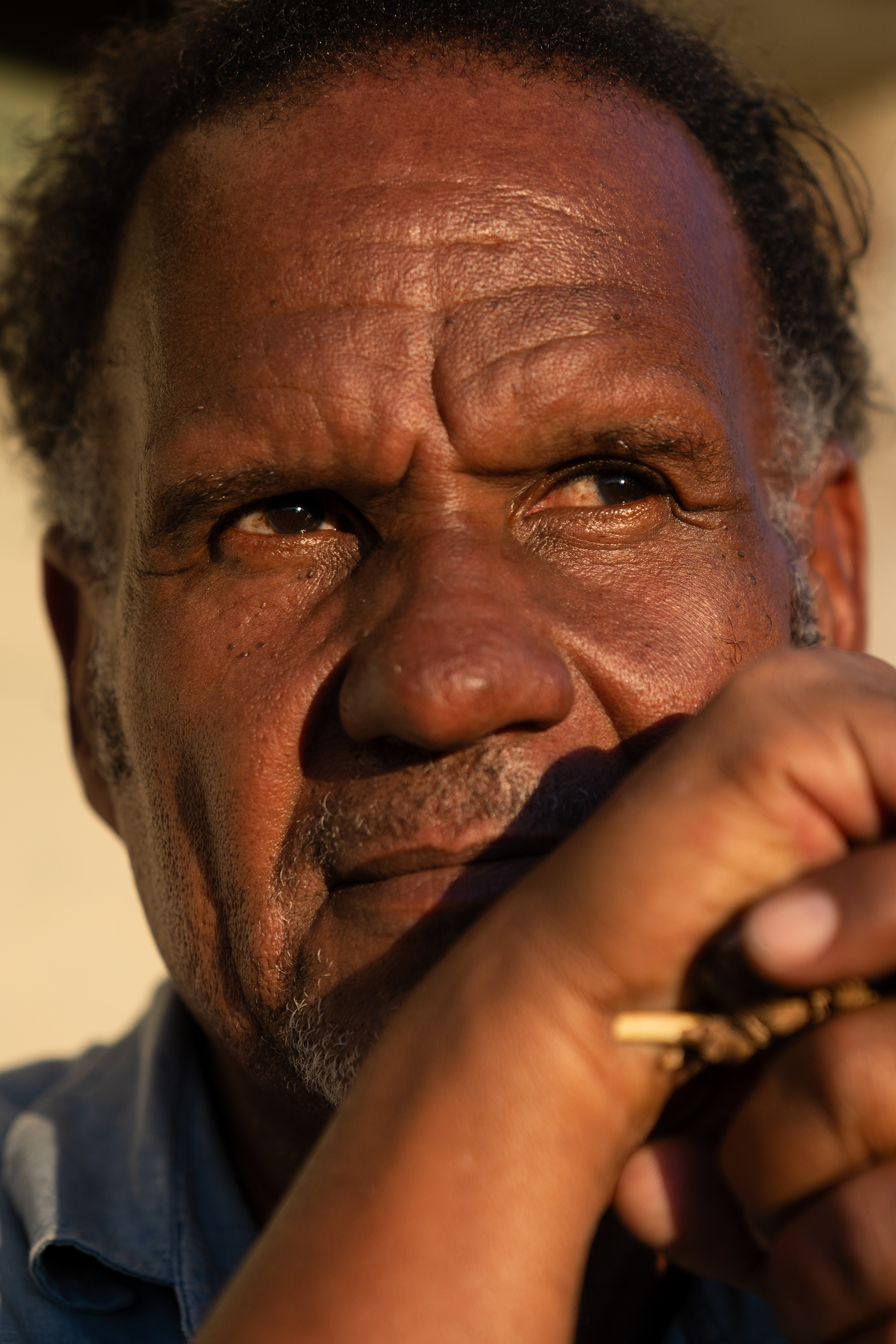

Orphaned early, Patrick grappled with identity and belonging, feeling disconnected from society and his roots. The absence of family left a void that shaped his withdrawn nature. Despite these hardships, he nurtured a curiosity for self-growth, finding solace in learning, art, and introspection.

"In many ways I’m still a child as I have so many more things to learn. I've tried to expand my way of thinking. I admire art, and read books. There’s something in a man that's meant to grow and change."

Aunt Maud proudly displays a newspaper clipping of her Gogo—a descendant of Matabele King Lobengula. She asserts: "I know, and admit, that I’ve got Black blood in me."

Aunt Maud grows pensive as she reflects on her complex heritage: "I am born of both Black and White. I was blessed, even though I was like a plastic bag blown from one thorn tree to another."

Despite his prejudice against interracial unions, Aunty Diana’s Scottish father had 32 children with his African wives. She recalls, “We felt unwanted by the Africans, and unwanted by the Whites, who were ashamed of us.”

Mrs Fransch recalls, "My father came up from South Africa when he was nineteen to look for work. Many young people came over to Rhodesia, as it was called back then, to look for work, you know? In those days, the only jobs that Coloured men could get were on the railway. And so, my father went to train with my grandfather, who was a plate layer."

"Growing up was difficult as I had no clue who I was, and where I came from. The connection between myself and society was quite difficult. Where do I fit in?"

![Aunty Edna examines an old sewing machine as she reminisces, "On our mother’s side, we had a Ndebele Gogo [Granny] and a British grandfather. Gogo learned to sew, so our grandfather bought her this sewing machine."](https://cdn.myportfolio.com/d284e763-b018-4ff9-a608-bb8c4aa3d74e/9ff89d79-4079-43ee-b700-0b27f3de7a7d_rw_3840.jpg?h=d793df62360e0d8db6ccdfca15c30107)

Aunty Edna examines an old sewing machine as she reminisces, "On our mother’s side, we had a Ndebele Gogo [Granny] and a British grandfather. Gogo learned to sew, so our grandfather bought her this sewing machine."

Uncle Petey strums his guitar on his porch. "Her name is Laura—the guitar," he says. "I used to collect country music records and perform at concerts."

As a teenager, Maud asked her aunt, “What does my mother look like?” Her aunt pointed to the mirror: “Look there.” For years, Maud searched the faces of White women in town.

"My siblings, children, grand-children, and great-grandchildren are spread out around the world–in Zimbabwe, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, and the UK. I have more photos of Kyle than anyone else. He kept me going, he's kept me alive."

![Sisters, Ethne and Edna, study an old photo album at their home. "Our paternal grandfather came from Madras, India, to South Africa. He worked as a chef on the railways in Cape Town, traveled to Zimbabwe by train, and married our grandmother, who was of Cape Coloured [from Cape Town, South Africa] and German descent. On our mother’s side we had a Ndebele Gogo and a British grandfather. Although our mother was bilingual, one of our sorrows is that we never learned to speak the Ndebele language."](https://cdn.myportfolio.com/d284e763-b018-4ff9-a608-bb8c4aa3d74e/29f1b3fb-926b-45c5-978c-31f08e8693fe_rw_3840.jpg?h=ec30ab0a9ac3d81857f85bc773076cdf)

Sisters, Ethne and Edna, study an old photo album at their home. "Our paternal grandfather came from Madras, India, to South Africa. He worked as a chef on the railways in Cape Town, traveled to Zimbabwe by train, and married our grandmother, who was of Cape Coloured [from Cape Town, South Africa] and German descent. On our mother’s side we had a Ndebele Gogo and a British grandfather. Although our mother was bilingual, one of our sorrows is that we never learned to speak the Ndebele language."

"The world is demanding and cruel. You have to overcome the barriers of your past so that at the end of the day you can be part of something."

At age thirteen, Mrs Fransch was sent to South Africa to train as a teacher because there were no high schools for Coloureds in Rhodesia, and no teaching colleges for them either. The government paid for everything, as White teachers wouldn’t work in Coloured schools. When she returned to Zimbabwe in 1950, Mrs Fransch taught until her retirement. "I knew every family in the neighborhood, because all their children had to come through me."

View full project here.